Hello everyone,

Hope you’re all doing well!

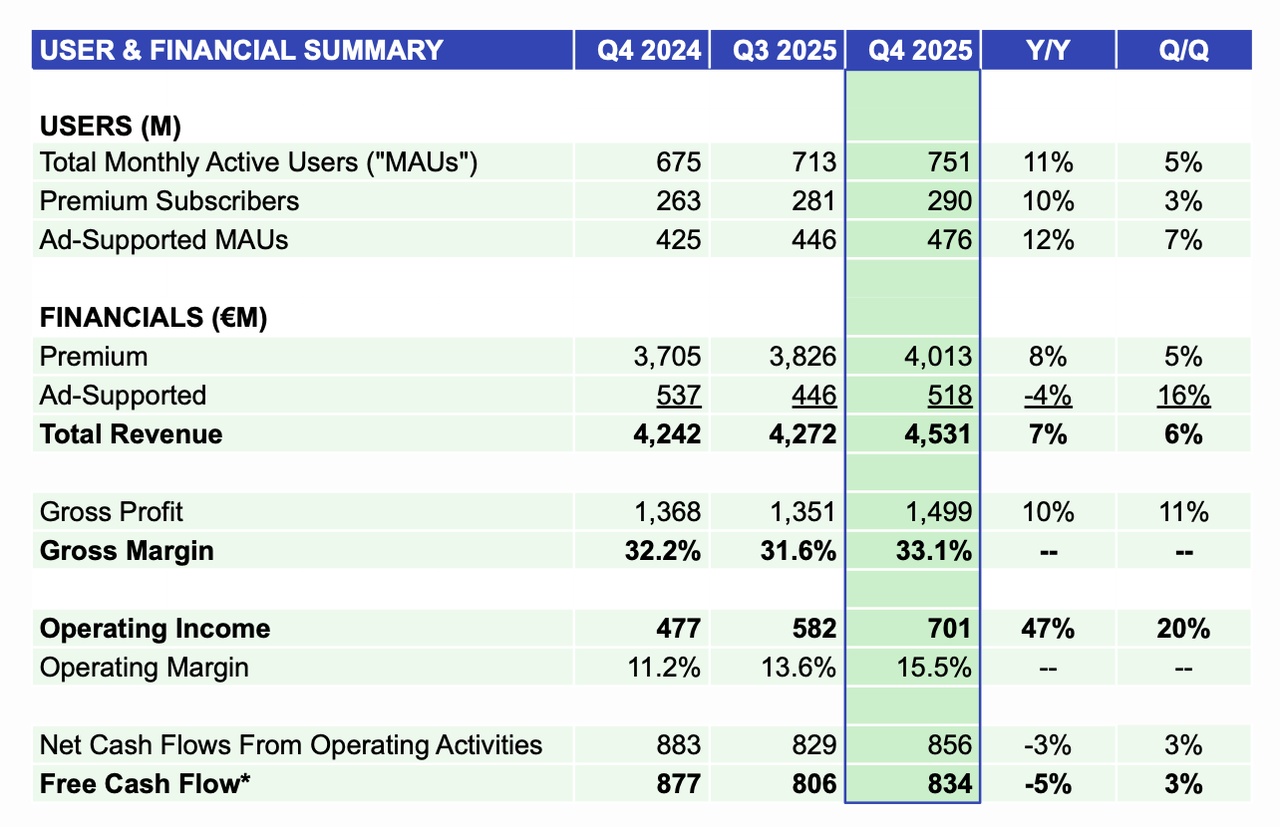

After doing some research and reviewing my portfolio, I’ve decided to close a few small positions and open a new position in $ADYEN (+3.82%)

For those who might not be familiar, Adyen is a Dutch payment technology company that provides a unified platform for businesses to accept payments online, in-app, and in physical stores. The technology handles everything from payment processing and risk management to acquiring and reporting, all through one integrated system — which makes it attractive for both large global brands and fast-growing platforms.

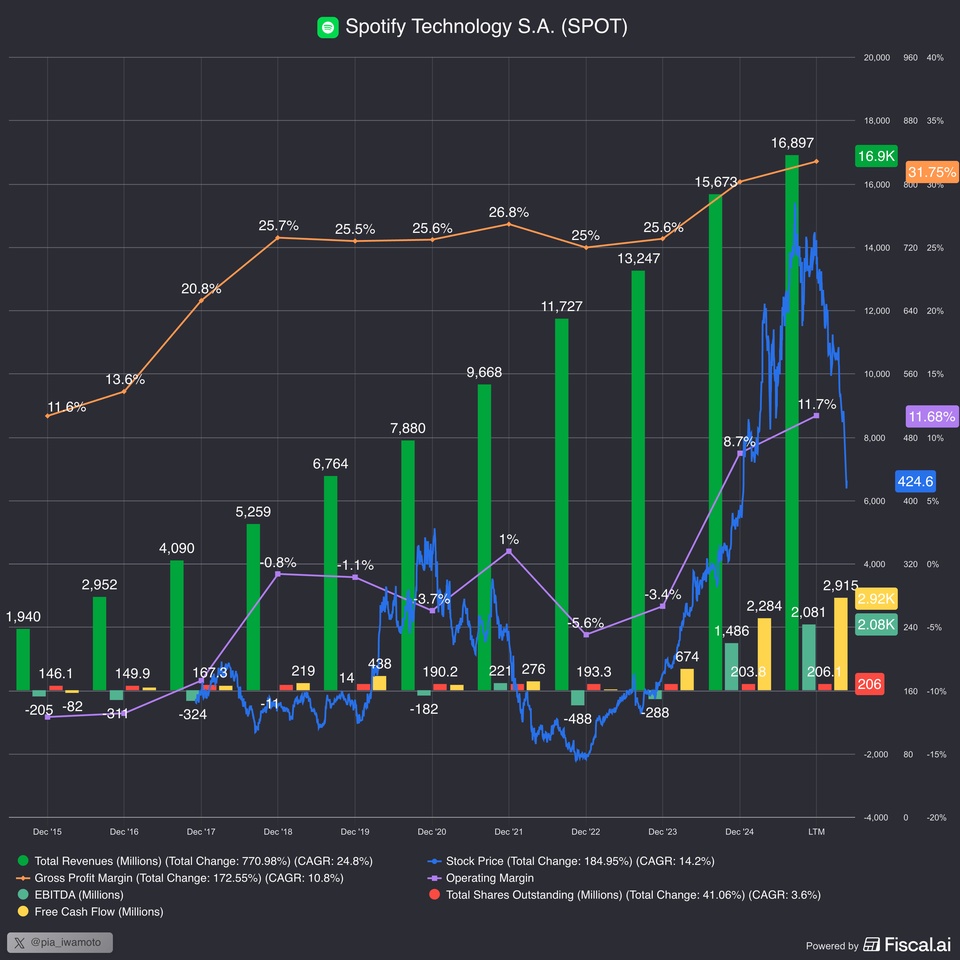

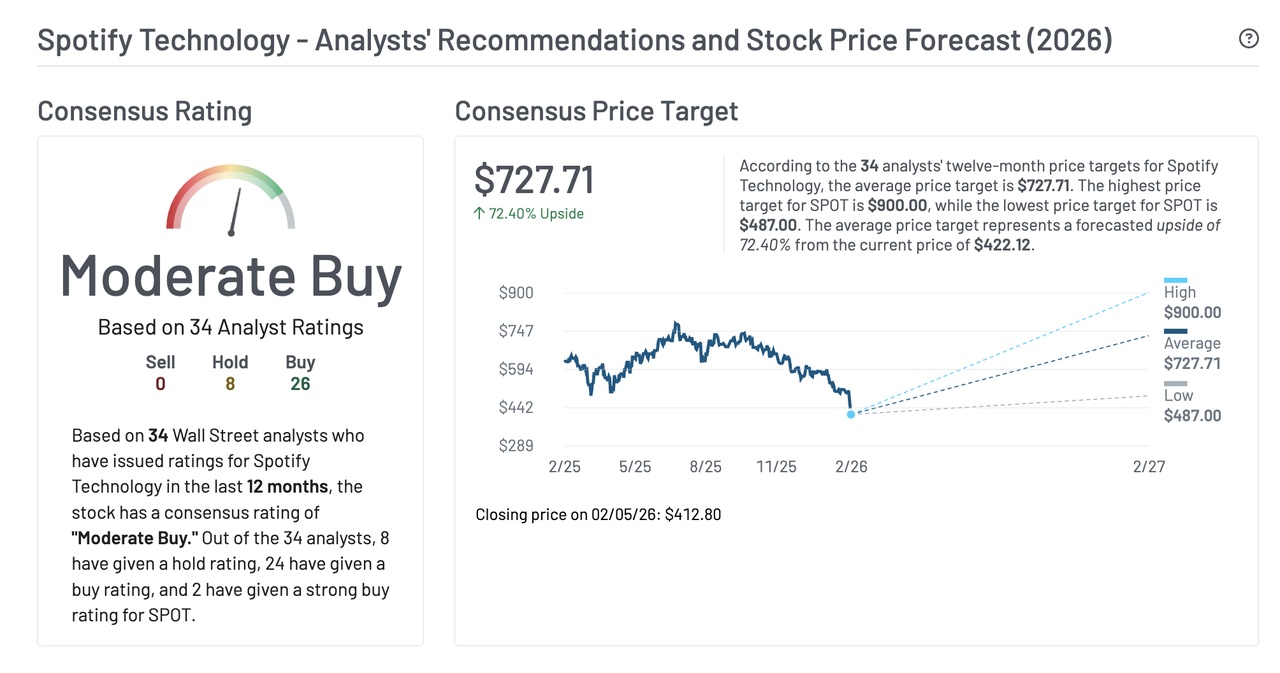

What really appealed to me is the calibre of companies that rely on Adyen’s platform. Some prominent global customers include $UBER (+0.52%) , $SPOT (+0.74%) , $MSFT (-1.73%) , $EBAY (-2.58%) and $HM B (-0.01%) — all using $ADYEN (+3.82%) to streamline their payments infrastructure across markets.

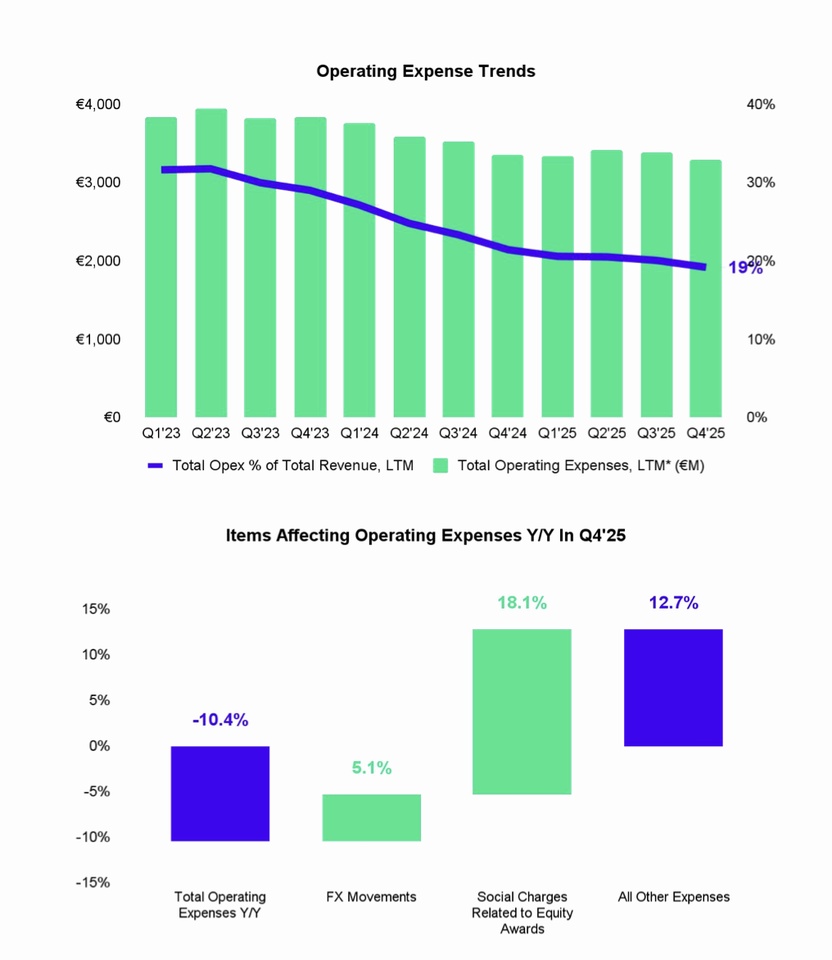

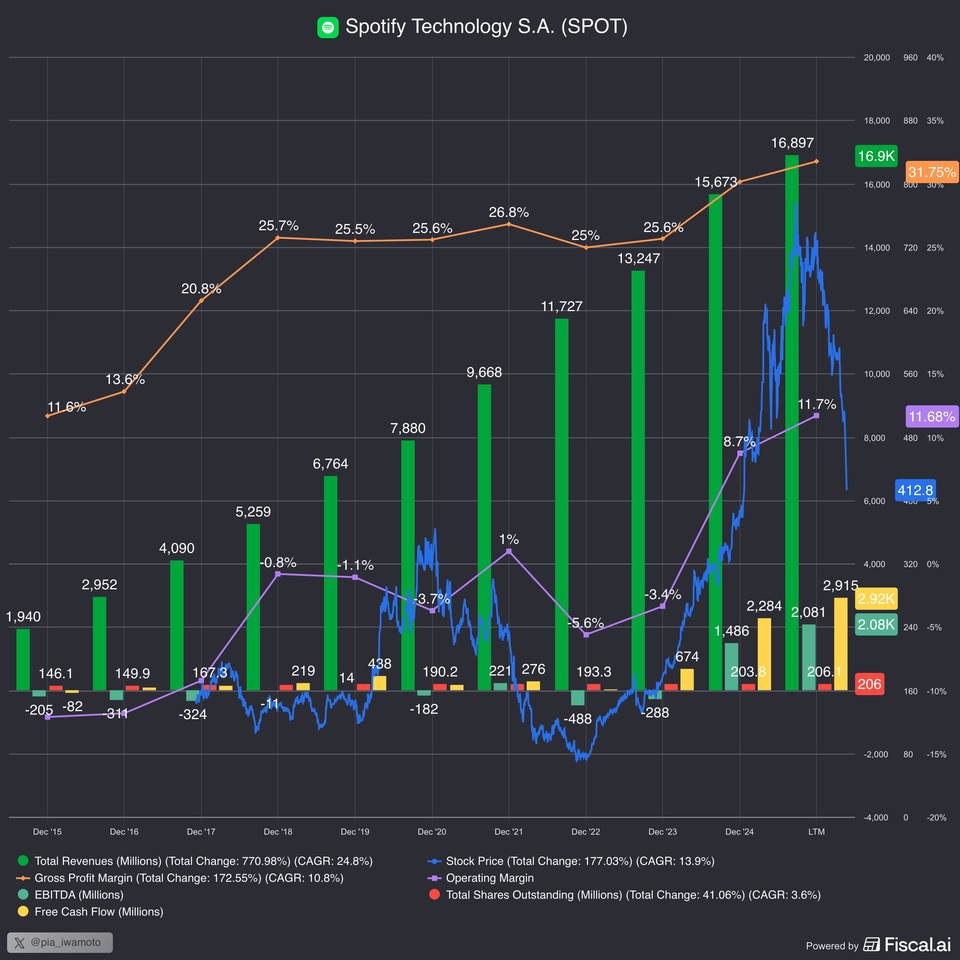

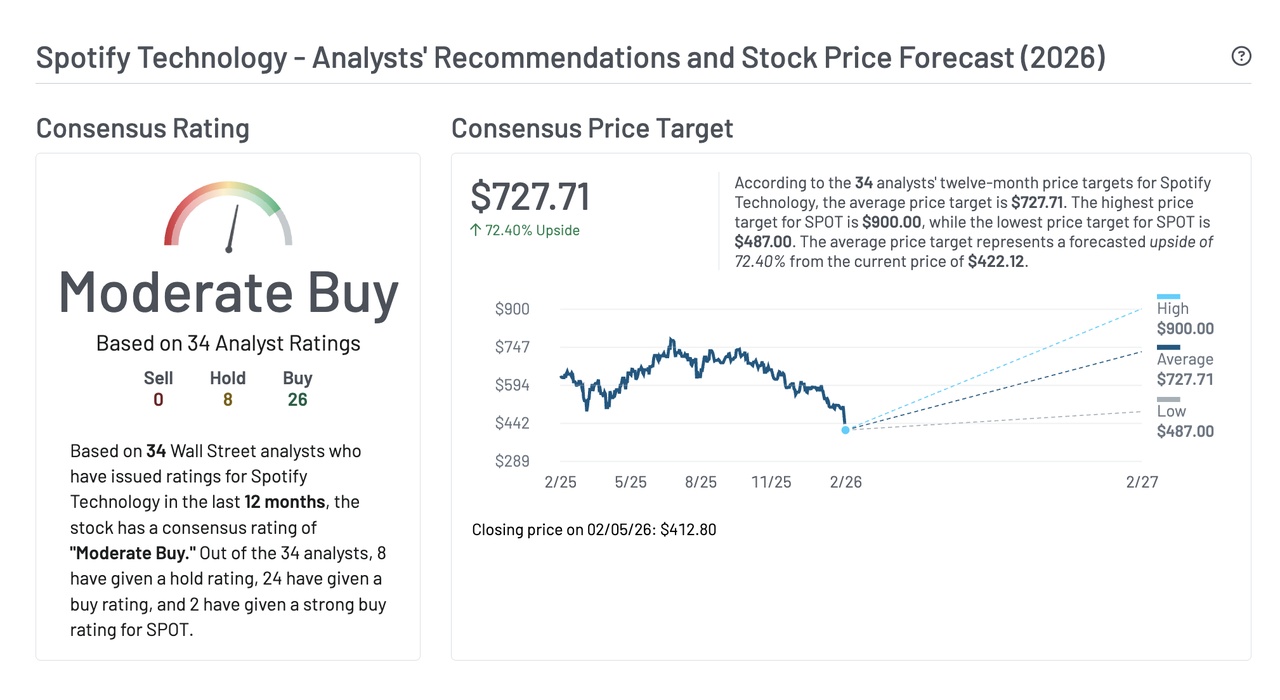

Over the past few years, the stock price has been quite the rollercoaster, with significant volatility reflecting broader market trends as well as shifts in the payments landscape. That said, I believe the long-term growth opportunities remain strong. As digital payments continue to expand globally and more merchants look to unified payment solutions, Adyen appears well-positioned to benefit from this trend.

Given the company’s fundamentals and growth potential, I think there’s a nice run ahead toward €1,700, and I’d really like to be along for that journey.

Curious to hear your thoughts — what do you think about Adyen as an investment? Do you believe the company is well positioned for future growth, or are there other players in the market that you think might outperform it?

Looking forward to your insights!

Cheers! 🚀