Reading time: approx. 4-5 minutes

I have written a lot about key figures in recent weeks and months. P/E ratios, ROIC, FCF yield, PEG, Rule of 40, interest rates, liquidity, market phases, multiple mechanics, volatility and fiscal policy.

Today I would like to bring it all together.

Because for me, the key insight from the entire series is not a single key figure. It is something more fundamental: key figures only develop their value in the right valuation framework. Without context, they are precise - but not necessarily meaningful.

Key figures measure conditions. Markets act on expectations.

The price of an asset results from the present value of expected future cash flows. Historical profits, margins or cash flows are important reference points. But they are not the future - they are only part of the information base.

A P/E ratio of 30 is neither automatically expensive nor automatically cheap. It is initially a relation between price and profit.

Whether 30 is high or low depends on the interest rate level, growth expectations, risk appetite and the business model. In an environment of low real interest rates, higher multiples are more understandable because the discount rate is low. If interest rates rise structurally, this logic changes. The same profit is discounted more heavily - the multiple falls, even if everything remains stable in operational terms.

With $MSFT (-0,48%) (Microsoft), a higher multiple may be plausible as long as returns on capital are significantly higher than the cost of capital. If the cost of capital rises, the economic leeway is reduced. The company remains qualitatively strong - but the valuation reacts to the framework.

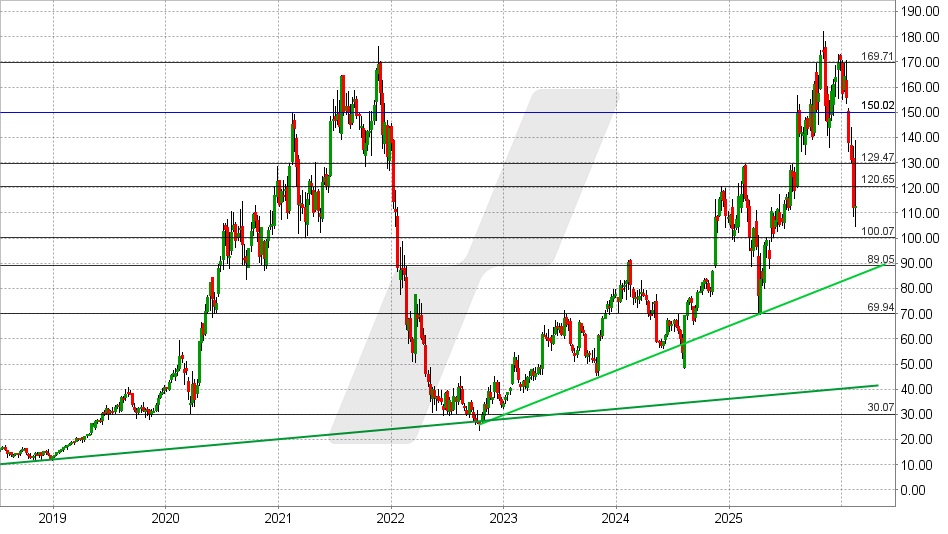

At $NVDA (-2,56%) (NVIDIA), we see how an investment cycle in AI infrastructure can carry a phase of multiple expansion. When growth or investment momentum normalizes, the perception changes. The multiple suddenly looks more ambitious - even though the metric itself appears unchanged.

Or let's take $XOM (+0,63%) (Exxon Mobil). A high FCF yield can arise in a high price phase. That looks attractive. But commodities are cyclical. Cash flows at the peak are often not sustainable. The key figure is correct - its interpretation depends on the cycle.

In the series, I have therefore presented a four-phase model: Build-up, Acceleration, Euphoria, Top. Not as a rigid scheme, but as an aid to interpretation.

Sales growth of 20 % can be seen as very positive in an early phase. In a later phase, the same figure can be perceived as insufficient. The key figure remains the same. The context changes.

Even the PEG ratio is only as good as its assumptions. With $SHOP (-3,23%) (Shopify), a normalization of growth can worsen the PEG without structurally damaging the business model. Forecasts are always subject to uncertainty.

A particularly central point is the relationship between return on capital and cost of capital.

A ROIC of 15 % sounds strong. If the cost of capital is 14 %, there is hardly any economic added value. An ROIC of 12 % can be significantly more attractive if the cost of capital is 6 %. The spread is decisive - not the isolated figure.

At the same time, precision remains important. A structured valuation model helps to make assumptions transparent. Sensitivity analyses show how strongly valuations react to changes in interest rates or margins. It only becomes problematic when the apparent accuracy of the output figure masks the uncertainty of the input assumptions.

The overriding insight is therefore: figures are necessary, but not sufficient.

An investor without key figures loses orientation. An investor with key figures, but without an evaluation framework, runs the risk of developing a false sense of security. Quality arises from the interplay of quantitative analysis, macro understanding, cycle awareness and business model analysis.

The question of whether the P/E ratio is 28 or 30 is not decisive in the long term. What is more important is the market framework in which we operate. Which phase dominates? How are interest rates and liquidity developing? Is the ROIC sustainably higher than the cost of capital? How sensitive is the valuation to changes in assumptions?

This series began with interest rates and liquidity. It then moved on to market phases and valuation mechanics and finally to individual key figures. If I could summarize everything in one sentence, it would be this: Key figures are tools. The valuation framework is the architecture in which they are used sensibly. Classification increases the informative value of key figures. Context structures precision.

If we take this idea further, the question arises as to the next logical steps. Here are four possible directions for the next series:

1. decision architecture in the portfolio

How do I define entry zones along scenarios? How do I determine position sizes depending on uncertainty? How do I deal with winners such as $MSFT (-0,48%) (Microsoft), which are ambitiously valued but remain structurally strong?

2. valuation mechanics & sources of returns

What is the composition of long-term performance? How much return on $AMZN (-2,34%) (Amazon) come from earnings growth, how much from multiple changes? When does earnings growth dominate, when valuation adjustment?

3. cycle investing without market timing

How do I differentiate between $XOM (+0,63%) (Exxon Mobil) structural quality from cyclical exaggeration? What role do earnings revisions play? How do different sectors behave in different phases?

4. quality vs. valuation

When is a valuation premium justified for high returns on capital? When is quality systematically overpaid? How long can spreads between ROIC and cost of capital realistically persist?

I would be interested in your assessment.

Which of these four directions would you prioritize? Or is there a completely different topic that we should systematically explore in more depth?