Reading time: approx. 8min

1) Introduction

After I wrote an article some time ago on the topic "How do I determine the fair price of a share?", I would now like to discuss in a deliberately contrarian article why the criterion "price" is overrated in many cases when deciding to buy a share.

For me personally, the decision-making process for a purchase is as follows: I find an interesting company and take a superficial look at key figures such as sales growth, gross profit, EBIT margin, ROCE and free cash flow growth. If these key figures look promising, I start with a detailed analysis in which I analyze the business model, the company's competitive situation and generally try to assess as many qualitative characteristics of the company as possible. I then try to estimate future growth prospects.

If, after all this analysis, I come to the conclusion that the company is promising, then comes the real crux of the matter:

- what is the price?

- What is the P/E RATIO?

- Is the company just at the all-time high?

- Has the company already risen 20% this year?

All the analysis and then you come to the sobering realization that the company is trading at a P/E ratio of 40, is pretty much at an all-time high and has already experienced a rally of 20% in recent months.

So what to do? Wait for a 20% fall in the share price? Buy a competitor with a more favorable P/E ratio? Do nothing and just wait?

2) Price as a purchase criterion?

The price of a share is a snapshot in time. It changes constantly and fluctuates depending on the market situation and the quarterly report. Much more important than the price is the so-called internal earning power of a company. This results from the long-term (cycle-adjusted) profits over the next few years or decades.

For many investors, however, the price is the main argument for buying. True to the motto "the share is really cheap right now", i.e. worth buying. Numerous examples from the past show that this is often a fallacy. Just because something is cheap does not necessarily mean it is worth buying. Here is the example of $BAYN (-4.34%):

But is the price really so important that it should be the main criterion for buying or not buying something?

For many investors, an ETF on the MSCI World, S&P500 or the NASDAQ100 are much more tempting and safer than investing in individual shares. These are based on the indices of the same name, which are known to have performed very well in recent decades. Most indices are weighted by market capitalizationwhich means that the higher the market capitalization, the higher the share in the index.

Isn't it strange that these indices weight shares higher when they have performed better and the higher the price increase? None of the known indices pay attention to the P/E ratio or similar key figures such as free cash flow yield when weighting. None of these indices look at quarterly reports or include management statements in the purchase decision.

These indices function as approximations according to the principle "what has a certain size and has done well will continue to do well". Essentially, they follow the following approach buy and hold. They only drop out of the index when the price of the company has fallen so much that they are too small for the index or they no longer meet certain quality standards - for example in terms of accounting. The winners are retained and the biggest losers are replaced.

3) Compounding

Not only since last year have we known that the performance of large indices such as the S&P500 is driven by a handful of companies. Last year it was the so-called Magnificant 7that delivered a large part of the performance, but at other times in history, too, it was always a few companies that made up the bulk of an index's performance.

What are the characteristics of such companies? They have been identified early and independent They were included in the index at an early stage, regardless of any P/E ratios, and held there according to the "buy and hold" maxim. If the company then performs well over the years, the weighting automatically increases and makes a greater contribution to the performance of the index as a whole.

Such companies are known as compounders. They have the characteristic that their profits regularly and disproportionately and that these profits are also highly profitable in the company's own business model reinvested business model - keyword: ROCE (return on capital employed). This means that future profits will be even higher and the higher profits can be reinvested in your own company in a highly profitable manner, etc. If the company is able to maintain this process over years or decades, it will outperform other companies. In the long term, the profits of such companies grow exponentially.

In summary, compounders have the following characteristics:

- over years/decades Stable business model

- above-average profit growth

- Profits can be highly profitable reinvested in the company's own business model

4) What prevails? A few examples

The price of such compounders is often significantly higher than that of comparable companies. Especially in comparison with companies of poorer quality. Does the price or the quality of the company prevail in my purchase decision? Is it better to buy an average company at a P/E ratio of 10 than a far above-average company with a P/E ratio of 40? Let's take a look at a few examples.

One company in my portfolio is $KLAC (+1.83%) a manufacturer of high-tech equipment and service provider for semiconductor fabs. In March 2001, the company was trading for a P/E ratio of about 230 at a price of about 70$ per share [2]. Today, some 23 years later, the company trades at a price of approximately $690 [1]. This is an annualized return of 10.5% compared to an annualized return of 6.7% for the S&P500 over the same period [1]. At the time, KLA could even have been valued at a P/E ratio of 450 and would still have outperformed the S&P500. An increase in the share price of 1% today (i.e. $6.90) corresponds to an increase of around 10% on the share price of $70 at the time.

Finding similar examples is not as difficult as one might initially think:

L'Oreal $OR (+1.71%) could have been bought in 2005 at a P/E ratio of 29 and would have outperformed the S&P500. In fact, L'Oreal could have been bought at a P/E ratio of 20 [1],[3].

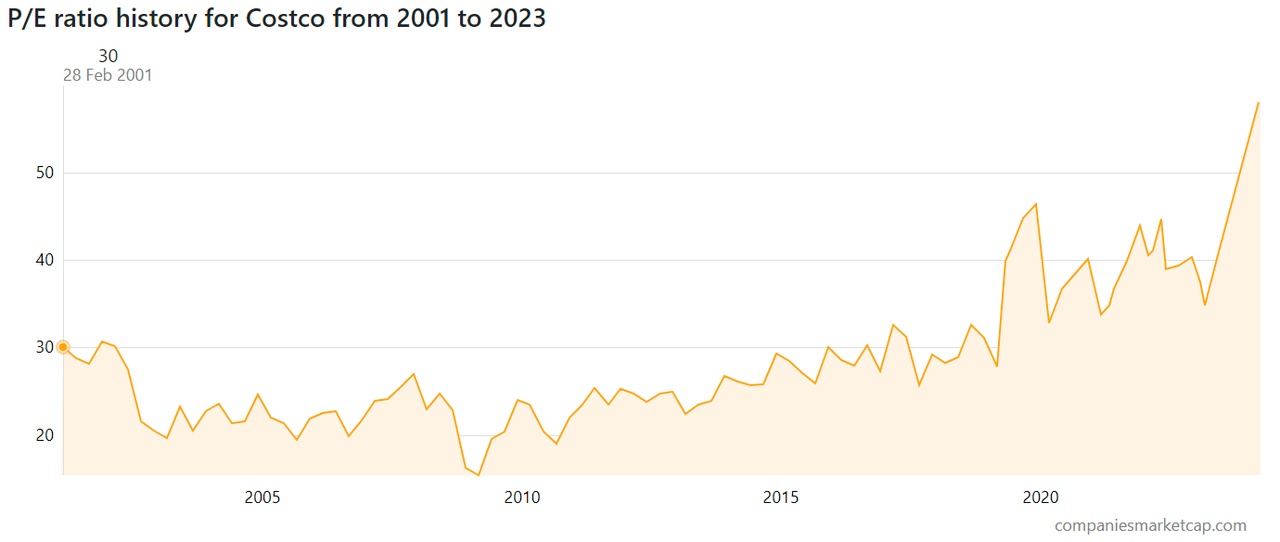

Costco $COST (-0.19%) could have been bought in 2001 at a P/E of 130 and would have outperformed the S&P 500. In fact, Costco was trading at a P/E ratio of 30 at the time, so you could have bought the stock at around 4 times that price and still outperformed the S&P500 [1],[4].

Mastercard $MA (+1.25%) went public in 2006. You could have bought it at a P/E ratio of 810 and still outperformed the S&P500 over the same period. In fact, Mastercard was trading at a P/E ratio of 210 at the time [1],[5].

All these examples are not about the discussion along the lines of "if I had bought 10 Apple shares in 1994, I would be a millionaire today". Rather, the observation is that neither the business model nor the characteristics of the example companies have changed significantly during this period.

KLA, L'Oreal, Costco and Mastercard do pretty much the same today as they did 20 years ago, were already capital-efficient back then and were able to reinvest their profits highly profitably in their own companies. Even back then, these companies had the characteristics of a compounder and over the period under review, they simply did exactly what compounders do: Reinvest profits lucratively in their own business model over long periods of time.

5) Summary & conclusions

In my opinion, the current price as a purchase criterion overvalued for companies with high quality. Buyers often focus too much on the price, i.e. the current valuation of the company, instead of focusing on the quality of the company. This sometimes leads to the exact opposite: supposedly supposedly companies are bought because they look cheap compared to compounders.

I personally therefore focus primarily on companies that offer high quality and have a high capital efficiency capital efficiency. I concentrate on the business model and key financial figures. The price is initially secondary and does not play a primary role in my decision-making process for a purchase. The higher the quality of the company, the more expensive it can be. Conversely, I don't buy companies just because they are cheap. I buy quality companies at a fair price and ideally keep them in my portfolio for years or decades.

Thank you for reading,

Yours Michael Scott

Sources:

[2] https://companiesmarketcap.com/kla/pe-ratio/

[3] https://companiesmarketcap.com/l-oreal/pe-ratio/